Caravanserais: The Original Motorway Service Stations.

Before lattes and fuel pumps, there were caravanserais — and it was in the lands that now form much of Afghanistan that the idea first took shape.

The word caravanserai carries more than just a literal meaning. Kārvān derives from Old Persian karwāna, meaning a group of travellers or merchants moving together, usually for mutual protection. The same root appears in Sanskrit (karabha, to move or travel). Sarāy means a house, palace, or enclosed space — but importantly, in both Persian and Turkic traditions, sarāy also referred to royal or administrative compounds. The famous Sarai Batu and Sarai Berke, capitals of the Golden Horde Mongols, both took their names from this word. Sarāy was not just any house. It often implied a place of importance, power, or protection. Thus, kārvān-sarāy originally signified not merely a shelter, but an official or respected space where travellers could expect both security and services.

When modern travellers pause at motorway service stations or rest stops, they are following a pattern older than they realise. The practice of building resting places along major transport routes — offering food, shelter, and protection — did not originate in the industrial age. Its origins lie deep in antiquity.

The earliest formal systems of waystations can be traced to the great empires of the ancient Near East. Yet it was in the lands of eastern Persia — encompassing much of what is now Afghanistan — that these simple posts evolved into the caravanserai: an institution that would become essential to the world’s great overland trade networks.

The story begins with the Achaemenid Empire in the 5th century BC. To govern an empire stretching from the Indus Valley to the Aegean, the Achaemenid kings built the Royal Road. Along its 2,400 kilometres, they constructed chapar khana — courier stations providing fresh horses and lodging for royal messengers. The Green historian, Herodotus, writing in the 5th century BC, praised the efficiency of these couriers, whose motto — “Neither snow nor rain nor heat nor darkness stays these couriers from swift completion of their appointed rounds” — would be borrowed, centuries later, by the United States Postal Service.

But these early waystations were exclusive. They served the needs of the state, not private merchants, pilgrims, or scholars. Ordinary travellers remained exposed to the dangers of the road: theft, illness, starvation, and fatigue. For centuries, while empires rose and fell, this basic limitation persisted. A critical innovation was needed — not simply a place to change horses or deliver royal decrees, but a secure, multifunctional hub where commerce and culture could flourish.

The origins of such roadside structures, however, stretch back even further. Archaeologists have uncovered an early antecedent of the caravanserai at a Urartian site in western Iran — near the mountain pass between Urmia and Oshnavieh — dating to the 8th or 9th century BC. These were likely fortified rural compounds that offered protection to travellers and their animals, long before the Silk Road took shape. But while these early examples marked the architectural seed, it was in the lands of eastern Persia — encompassing much of what is now Afghanistan — that these simple posts evolved into the fully-fledged caravanserai: fortified, multifunctional, and essential to global trade.

That innovation took place not in the imperial capitals of Mesopotamia or Anatolia, but further east, along the great arteries of the Silk Roads where Persia met India, Central Asia, and China. Classical geographers knew this region as Ariana or Bactria; later Islamic scholars called it Khorasan. Its major cities — Herat, Balkh, Kandahar, Merv, and others — were ideally placed at the crossroads of trade. Goods from the Mediterranean, East Africa, and Arabia flowed eastward through Persia into Central Asia and beyond, while silks, spices, gemstones, and intellectual traditions moved west.

By the time of the Kushan Empire, in the 1st to 3rd centuries AD, the demands of this exchange required more structured infrastructure. The Kushans, ruling from their summer capital at Bagram (near modern Kabul), oversaw a domain that linked the Indian subcontinent to the broader Silk Road. It was under their rule that the basic wayside inn evolved into a fortified compound.

These early caravanserais weren’t just shelters. They were enclosed complexes offering stables, wells, food, and lodging. Artisans repaired goods; merchants rented space to trade. Some included shrines or prayer rooms. The archaeological discoveries at Bagram — including Roman glassware, Indian ivories, and Chinese lacquerware — suggest the kinds of interactions these posts facilitated.

By the early medieval period, the caravanserai had matured into a cornerstone of Eurasian commerce. Under the Samanid dynasty (9th to 10th centuries) and later the Ghaznavids (10th to 12th centuries), who ruled from Balkh and Ghazni, the system was formalised. Caravanserais were now spaced at predictable intervals — usually a day’s journey apart — allowing caravans to rest, resupply, and travel with a rhythm that enhanced both security and speed.

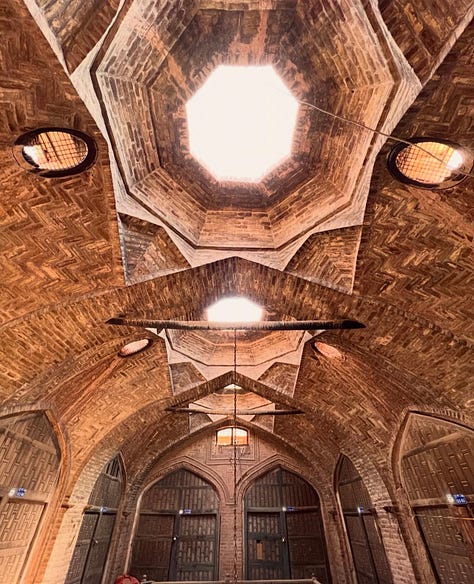

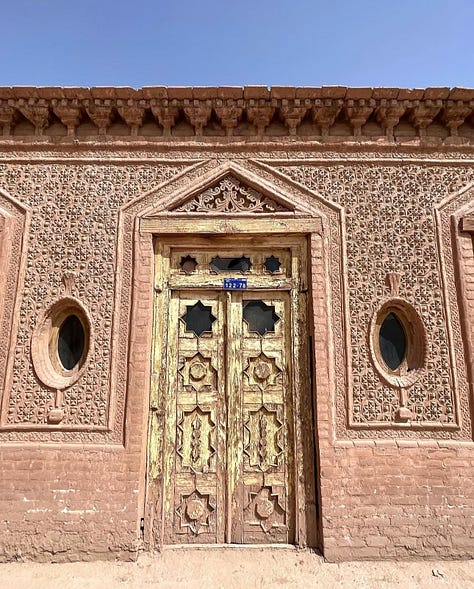

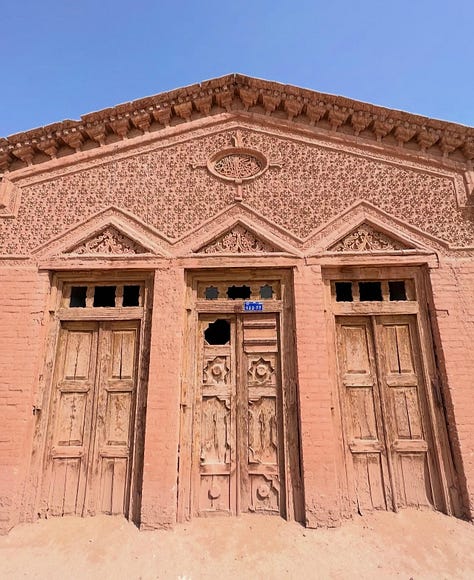

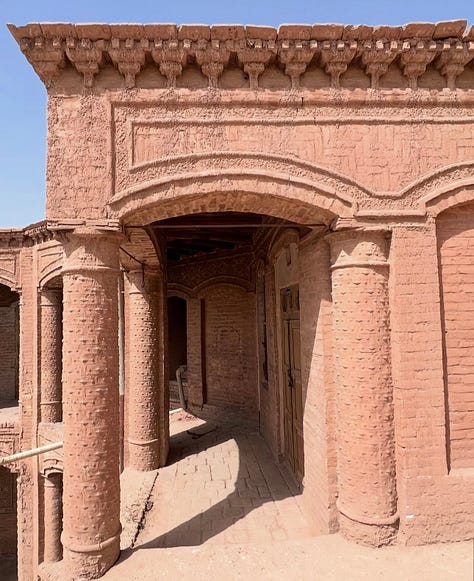

The architecture became standardised. A heavy gate led into a spacious courtyard, where animals were tethered and goods unloaded. Living quarters lined the interior walls; storerooms and stables flanked the corners. In large cities like Herat or Balkh, caravanserais grew into semi-autonomous districts. Blacksmiths, cobblers, translators, money-changers, even doctors — all operated within these self-contained worlds.

These were not merely commercial spaces. Caravanserais became cosmopolitan microcosms. A Sogdian trader from Samarkand might share supper with a Tamil merchant from the Coromandel coast. Nestorian missionaries met Buddhist monks. Persian mingled with Greek, Arabic with Sogdian. Silk and turquoise changed hands alongside stories, cures, and maps. Caravanserais weren’t just logistical marvels. They were incubators of pluralism — places where ideas moved as swiftly as merchandise.

As the Islamic Golden Age expanded west, so did the caravanserai. The Seljuk Turks, whose empire extended from Khorasan into Anatolia, commissioned monumental roadside inns across Iran and modern Turkey. These were state-funded, fortified, and often endowed to serve travellers for free. The Ottomans inherited this tradition. In Istanbul, the great hans became part of the city’s commercial fabric, while provincial caravanserais appeared across the Balkans.

Further east, the Mughals adapted the model for the Indian subcontinent. Emperor Sher Shah Suri built hundreds of saraisalong the Grand Trunk Road in the 16th century — each spaced roughly every 2 kos (about 7 km) and offering water, shade, food, and security. His successor, Jahangir, ordered that all sarais be constructed in stone and provided with staff. From Kabul to Bengal, the road became a lifeline of empire, stitched together by the caravanserai.

Though the caravanserais of Greater Khorasan and beyond now lie in ruin, their logic endures. The notion of building places where travellers rest, resupply, and reconnect remains central to modern mobility and travel infrastructure. Many of these caravanserais can still be visited today. In Iran, cities like Isfahan, Qazvin, and Kashan are home to beautifully preserved compounds. In Samarkand and Bukhara, too, the old Silk Road lives on in stone. These cities remain among the best places to walk through the spaces where merchants once gathered, rested, and traded. I only hope that archaeologists will be able to carry out more fieldwork in modern-day Afghanistan, where so much of this history began — and where so much of it has been buried, forgotten, or left unexamined.

And perhaps that’s why it is so often overlooked. Ancient and medieval histories still begin with Roman roads or European merchant guilds.

Today’s motorway service stations, highway rest areas, and even airport lounges are modern echoes of this ancient design. The architecture has changed. The camels are gone. But the principle remains: human movement requires sanctuaries. Trade demands trust. And both were first institutionalised in the caravanserais of the Persianate world.

NOTE TO READER:

History has always been taken from us — written by them, for us. The real stories were never recorded. Or worse, erased. My writing is an attempt to bring back to life what the history books left out.

I write these pieces without funding or institutional support, but out of a need to reframe — and reprogram — how we see places like Afghanistan. Not through the lens of war, but through the lives, stories, and histories that rarely make it to you. As a woman from Afghanistan and an aspiring historian, I’m building something that doesn’t yet exist.

If this piece moved you, consider becoming a paid subscriber. It helps keep this work independent — and ensures these stories continue to be told to a global audience.

But most importantly, I hope you’ll read, reflect, and share — because history belongs to all of us.

When I was a child I thought it would be nice to live in Victoria station: there were cafes, a bookshop, even a cinema, plus lots of people coming and going. Sounds like a modern caravanserai.

One former Caravansaray is now a hotel in Amed aka Diyarbakir, eastern Turkey.. I stayed there last week.. The rooms are basic but the courtyard is magnificent, allowing you to visualize how it must have been during Silk Road times..