How a polymath from Balkh invented the modern perfume

The liquid perfumes we use today — and which Europe claims as its own — began in the laboratories of medieval Persia, created by a genius who came from what is now Afghanistan.

When people think of perfume, they think of France and Italy.

Parisian fashion houses. Provençal lavender fields. Glass bottles lined behind polished counters.

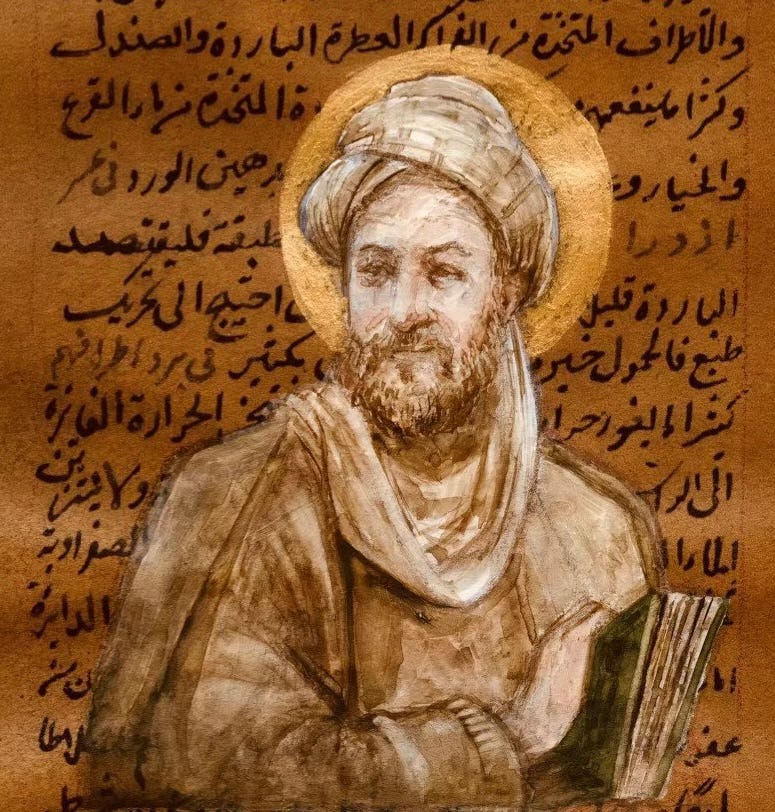

But the true origins of modern perfumery lie far from France. They lie in the laboratories of medieval Persia. And with one remarkable man. Avicenna. A physician, philosopher and scientist, born into a family from Balkh, once called the "Mother of Cities", now a crumbling, overlooked corner of northern Afghanistan.

The desire to capture scent predates Avicenna by millennia. Around 1200 BC, in ancient Babylon, one of the earliest recorded female chemists, a woman named Tapputi-Belatekallim, distilled flowers, oils and resins. Her name, recorded on a cuneiform tablet, suggests she held a senior role at court. Tapputi’s methods were skilful but rudimentary. Aromatics were mixed with water, solvents and animal fat, producing heavy ointments worn on the body in thick layers rather than the light fragrances we recognise today.

For centuries, little changed. Across Mesopotamia, Egypt and the Mediterranean, perfumes were coveted, but production methods remained crude. A breakthrough was needed. A gentler, more precise way to draw scent from flower and leaf.

It came in Persia, around the turn of the first millennium. And when I say Persia, I do not mean the borders of modern Iran. At that time, Persia was a vast cultural and intellectual world stretching across what is now Afghanistan and beyond.

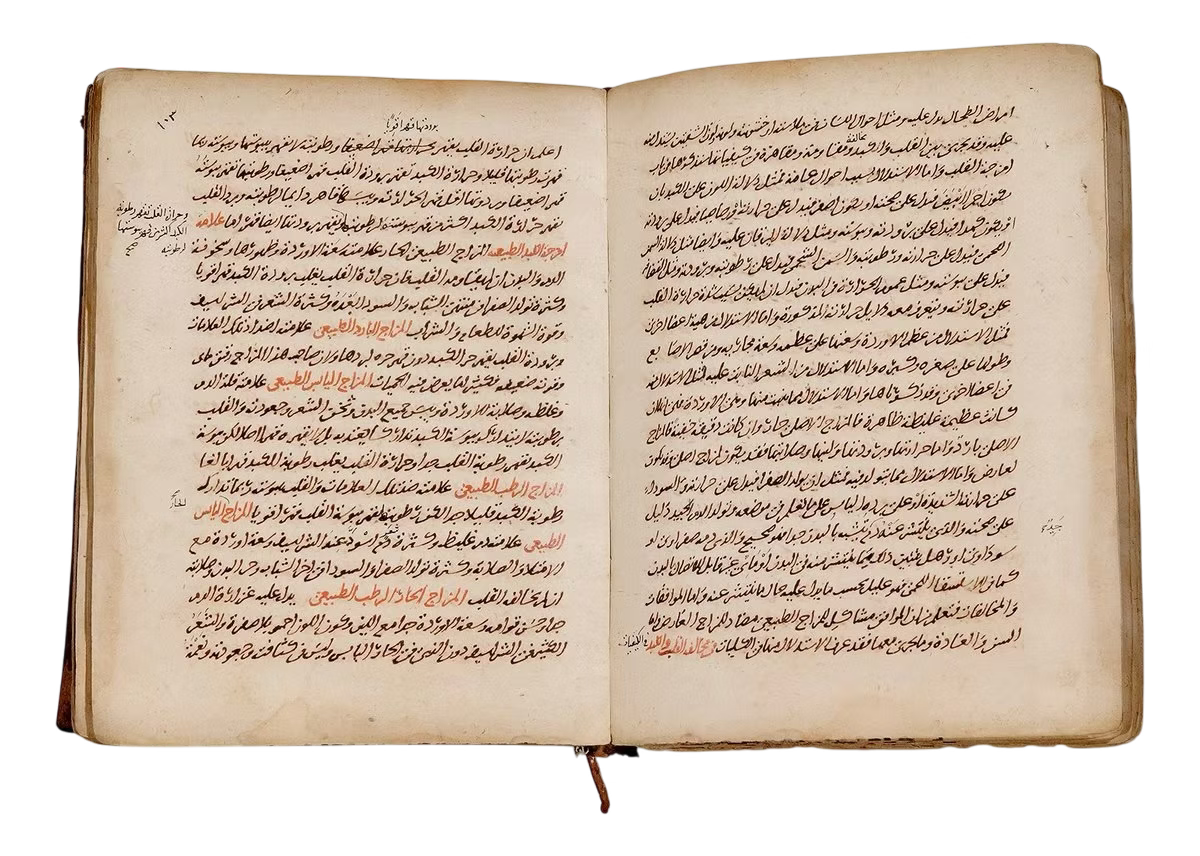

Abu Ali al-Husayn ibn Abdullah ibn Sina, known to the Latin-speaking world as Avicenna, grew up surrounded by Persian intellectual traditions. His family had deliberately moved to Bukhara, the capital of the Samanid empire, where major scholars gathered. His father, a civil servant from Balkh, ensured that learning shaped his early years. In his autobiography, as recorded by his student al-Juzjani, Avicenna recalled that his father surrounded him with scholars and encouraged him to study not only religion but also logic, philosophy, mathematics and the natural sciences. By the age of sixteen, Avicenna had mastered philosophy and medicine.

At eighteen, he treated the Samanid ruler (Emir Nuh II) for an illness that had baffled court physicians. His reward was rare. He was granted access to the Samanid royal library in Bukhara, which was one of the greatest collections of its time, rivalling the Bayt al-Hikma in Baghdad and the Fatimid libraries in Cairo. The library contained not just Persian and Arabic works but also Greek, Indian and even earlier Mesopotamian knowledge that had been translated into Arabic or Persian during the great translation movement of the Abbasid era.

This library exposed him to texts that were not available to most scholars.

They gave Avicenna access to the cutting edge of multiple civilisations’ thought, which he later synthesised into the philosophical and medical canon that would shape both the Islamic world and Europe’s Renaissance.

Among the many fields he mastered, one of his innovations would leave a quiet but lasting legacy. Drawing on the scientific traditions he had found in the royal library, Avicenna refined the technique of steam distillation. He applied it first to rose oil. By using steam to extract volatile oils from plant matter and then condensing the vapour, he captured the pure essence of flowers.

No more reliance on animal fats or oily bases. For the first time, scent became light. Portable. Enduring. Fragrance was no longer bound to ointments or pastes. It could move with a person, catch on the air and linger.

Avicenna’s method spread quickly across the Islamic world, where perfumery was already highly developed, then westward to Europe via Sicily and Spain. By the Renaissance, Italian and French perfumers were using steam-distilled essences, laying the foundations of today’s fragrance industry.

That part of the story is well known.

What is less acknowledged is the chapter that came before. Our chapter.

Western histories of perfume often begin in Renaissance Italy or 18th-century France, as if the centuries of knowledge that preceded them were footnotes. Without Avicenna’s work and the scientific culture of medieval Persia, modern perfumery would not exist.

Balkh, the city his family came from, was once a great centre of learning. Its thinkers shaped philosophy, medicine, mathematics and the arts while much of Europe struggled to preserve the remnants of classical knowledge. But centuries of war, colonialism and modern neglect destroyed its physical institutions and erased recognition of the region’s contributions to the intellectual history of the world.

What remains today in my native homeland are ruins, often cited as proof of supposed backwardness. Yet the destruction came from outside, and its intellectual traditions have been rewritten or excluded from dominant historical narratives. The state of the city today reflects political choices and historical violence, not an absence of civilisation.

Now that you know this, the next time you enjoy your modern perfume — whether Chanel, Dior or Jo Malone — remember that a genius from Balkh made it possible. Remember this when you think of Afghanistan. What our people were capable of when education, knowledge and the freedom to be curious were permitted.

NOTE TO READER:

History has always been taken from us — written by them, for us. The real stories were never recorded. Or worse, erased. My writing is an attempt to bring back to life what the history books left out.

I write these pieces without funding or institutional support, but out of a need to reframe — and reprogram — how we see places like Afghanistan. Not through the lens of war, but through the lives, stories, and histories that rarely make it to you. As a woman from Afghanistan and an aspiring historian, I’m building something that doesn’t yet exist.

If this piece moved you, consider becoming a paid subscriber. It helps keep this work independent — and ensures these stories continue to be told to a global audience.

But most importantly, I hope you’ll read, reflect, and share — because history belongs to all of us.

Your words bring back the voices that were erased. That matters. 👏🏻

This post is very intriguing. I really enjoy it when people are bringing up older and forgotten history's.