Seven generations ago, my ancestors left Samarkand. I went back to find them

With no name, no grave, only a family tree drawn on paper — I set out to find the places my forefathers once called home.

Omar kaka (uncle, in Persian) pointed to the top of the paper, to a name I couldn’t pronounce, and asked me if I could read it. I hesitated. My reading Farsi wasn’t yet fluent. So he read it for me: Samarkand.

“Seven generations ago,” he said, “your forefathers came from there.”

He was an elderly uncle, in his eighties and now blind, sitting cross-legged by the window that overlooked the valley, a cup of green tea in his hand, his face turned gently toward the sun. Though he was blind, he could still write from memory — the names, the places, the family lines he had carried in his mind for decades.

He listened intently to the sounds outside — as if the valley itself were speaking to him. He smiled often. It was the kind of contentment I hadn’t yet learned to understand. Even then, I remember thinking how complete the moment felt — how little it required to be beautiful.

It was the summer of 2004 when I first returned to Afghanistan. I was thirteen years old. We had left when I was very young, and my memories of it were mostly made up of what I’d overheard in living rooms, watched on late-night news, or glimpsed through old photographs. That first trip, made in the long shadow of war, was my father’s attempt to ensure that we remained rooted — that the country would never become distant to us, even if we no longer lived in it.

We returned again the following year, and then again after that. By 2008, we had planned something different — a journey outside the capital, into the rural district of Ghorband, where my father had been born and raised.

The drive from Kabul was long and winding, passing through valleys where the dust clung to every window and the light shifted with the road. Ghorband is a district that still feels tucked away, as if folded deliberately into the hills to avoid the noise of the world. There, in a neighbourhood called Fondukistan — a name I only later realised held archaeological significance and was once an early medieval Buddhist settlement — every house, every path, every turn seemed to belong to someone related to us. That sense of familial saturation was something I had never experienced in London.

Everyone, it seemed, was either a cousin, an aunt, or a sibling removed by several generations.

We stayed in my great aunt’s flat-roofed, camel-coloured mud-brick house, perched on the edge of the valley — the kind of home that holds the day’s warmth in its thick earthen walls and exhales cool air by evening. The rooms were simple, the walls worn with age, and the view from the wooden window was a gentle tableau of cows, chickens, and the unhurried murmur of the nearby river.

It was quiet — the kind of quiet you don’t realise you’ve been missing until it wraps around you.

One afternoon, we visited him — the uncle — for the first time. And we returned twice more that summer. There was something about the way he spoke with my father — calm, deliberate, full of memory — that drew me in. I found myself asking my dad if we could keep going back to see him while we stayed in Ghorband.

On our third visit, the conversation drifted into the past. Omar kaka began to speak about lineage — how he and my father were connected, how the branches of our family had woven together over generations. Then, he asked for paper and a pen. Slowly, with the kind of care only age can teach, he began to draw a family tree.

I have forgotten many of the names he wrote. I wish I hadn’t. I wish I had folded the paper and brought it with me. But that moment — that name — stayed with me.

Just then, I remember being called by some of the girls and stepping outside, leaving the men to their talk. I wandered into the shared farmland with my female relatives, where the trees bowed gently under the weight of mulberries. We picked them straight from the branches, the fruit warm from the sun, staining our fingertips a deep, sticky purple. The laughter of the girls echoed between the orchards, but my mind was elsewhere. I thought to myself: there is so much I don’t know about who I am.

And I knew, even then, that the story of my ancestry stretched far beyond the hills I could see — beyond this valley, this village, and even this modern nation.

The memory stayed with me. Years passed. Afghanistan changed. So did I. And in 2022, I decided to take the step I had long put off — to travel to Uzbekistan.

I travelled with my parents and siblings, but in truth, it felt like a father–daughter journey. In many ways, we are alike — though he’s far more sociable than I am. He strikes up conversations with strangers on planes, in queues, at street corners. He’s endlessly curious about people, always listening, always engaging. I’ve inherited some of that curiosity, though mine tends to turn inward — into books, into research, into the quiet work of history and writing.

But what made this journey different was that, for my parents, it was also a kind of return. They had spent much of their youth in the former Soviet Union — travelling between Uzbekistan, Azerbaijan, Tajikistan, Ukraine and Russia. In the late 1980s, while Kabul was still caught in the ideological undertow of Cold War politics, they were studying, moving, building friendships across the Soviet republics. The Russian language, the long corridors of Soviet trains, the pale concrete architecture of cities like Tashkent and Dushanbe — all of it was deeply familiar to them. They had eaten plov in Bukhara. They had once boarded a train to Samarkand not as pilgrims, but as students.

What my father didn’t know then was that his ancestors had already walked those streets long before him.

For me, these places had always been mysterious — spoken of in passing, flickering in photographs, tucked between stories I half-remembered. For him, it was as though the map was folding back into itself. And so we planned the trip together, not as a holiday but as an investigation. Could we trace the thread from Ghorband to Samarkand?

We flew from London to Tashkent, where we spent a few days before heading to Samarkand and Bukhara. From Tashkent’s main train station — a vast Soviet-era building with wide tiled halls — my mother spoken to the cashier in Russian and we bought tickets for the three-hour journey to Samarkand. The carriage had bunk beds and duvets, old curtains drawn halfway, and an attendant, Dilnoza, who spoke in the soft Tajiki dialect of Persian. It felt, strangely, like home.

We spoke for hours with Dilnoza, exchanging stories about life before and after the collapse of the Soviet Union. They told us about their families, about how things had changed for them, about what had been lost. I listened carefully, aware of the similarities between their stories and those I had heard in Afghanistan.

The landscape outside the window — dry mountains, rolling hills, scattered villages — was not unfamiliar. I spent most of the journey in quiet thought, trying to picture the world my ancestor had left behind. What would have compelled someone to leave Samarkand seven generations ago? What paths might they have taken? What did they carry with them?

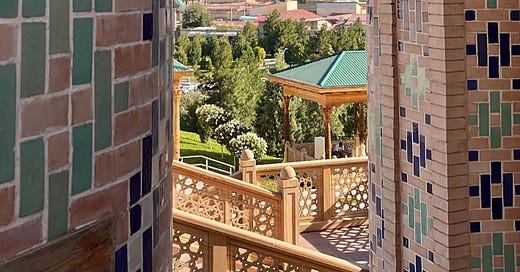

When we arrived in Samarkand, it was late. We took a taxi to our hotel, a traditional guesthouse built around a courtyard, its walls creamy, wooden panels, its ceilings painted in the old style. The streets we passed — narrow, dimly lit, lined with homes — reminded me of Ghorband. Something about the way the doors were built, the colour of the plaster, the low-hanging branches that curved over the road. I felt oddly at ease.

Samarkand, like Bukhara, was and still is a Tajik-majority city. Persian was once the language of the courts, the markets, and the streets. But in the early 20th century, during the Soviet division and redrawing of borders across Central Asia, Samarkand and Bukhara — historic centres of Persianate culture — were were incorporated into the newly formed Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic (Uzbek SSR). At the same time, the Tajik ASSR (Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic) was established within the Uzbek SSR — essentially making it a subordinate unit. In 1929, after pressure from Tajik intellectuals and political manoeuvring, the Tajik SSR was separated out and became a full republic — but without Samarkand and Bukhara.

What had been fluid borders became fixed lines. Language and identity became political.

Still, it surprised me how easy it was to communicate. The dialect had changed, softened, bent into its own shape — but I could understand most of what was said. We heard Tajiki in the bazaars, in the taxis, in the voices of children playing outside. I didn’t need Russian or English. Just the language I had grown up with.

Before we visited the famous sites, we spent a morning walking through the backstreets. Women stood outside their homes, chatting across walls. Children played football. Men sat quietly, sipping tea. There was a rhythm to it all — slow, settled, content. It reminded me of what I had felt in Ghorband. Of what I had seen in that small room, with the blind uncle and the view of the river.

We visited the Registan, of course. Shah-i-Zinda, too. The domes were more brilliant than I expected, the inscriptions more intricate — not just decorative, but purposeful. Above the entrance to the Ulugh Beg Madrasa, one read:

“The pursuit of knowledge is the duty of every Muslim man and woman.”

طلب العلم فريضة على كل مسلم ومسلمة

The phrase was written in bold Kufic script, set into ceramic tile mosaics — one of the earliest forms of Arabic calligraphy, all sharp angles and geometric precision.

Samarkand wasn’t merely a city of conquest and trade — it was a city built for learning. In the 15th century, under Ulugh Beg, it became one of the great centres of astronomy and science in the Islamic world. Here, the stars were charted, and scholars from across Central Asia gathered beneath turquoise domes to study the universe. It made me wonder whether my ancestor, whoever he was, might have once passed through these same archways in search of knowledge — or perhaps simply stood beneath them, in awe, like I was.

Samarkand has worn many identities across the centuries. In antiquity, it was the capital of Sogdiana, a satrapy of the Persian Achaemenid Empire. It later flourished under the Sassanids, then the Arabs, and eventually the Timurids. After a rebellion in 1365 against Mongol rule, Timur — the great conqueror known in the West as Tamerlane — claimed the city as the capital of his empire. From Samarkand, he ruled a vast stretch of Central and South Asia.

He brought architects from Shiraz, calligraphers from Baghdad, and scholars from Damascus. He filled the city with minarets, madrasas and mausoleums — their blue tiles still dazzling under Uzbekistan’s sun.

Its monuments are still vast. The Registan — a trio of madrasas built between the 15th and 17th centuries — feels like an open-air theatre of geometry and calligraphy. Its symmetry is mesmerising. At Shah-i-Zinda, a necropolis of tiled tombs, we wandered through a long corridor of domes built for queens, saints, and astronomers.

And yet, it was the ordinary moments that stayed with me — the sound of a language I recognised, the smell of bread baking in clay ovens, the quiet certainty that this place had once been ours.

Who was he, my forefather? Was he a poet, a merchant, a scholar, an amir — or just an ordinary man who once walked these same streets? My next mission is to try and find out. Maybe I’ll be able to trace the lineage more precisely, or even track down relatives still living in Ghorband who remember more than I do. Or maybe I won’t. Maybe all I’ll ever have is this memory — of a hand-drawn family tree, a blind uncle by a window, and a city that somehow felt like home.

The recent quest was never really about finding a name or a grave. It was about something more fragile — trying to trace what survives when everything else is gone. I can’t search for my forefathers on ancestry websites the way a European might — or even as many in neighbouring countries like Iran or Pakistan often can. There are no diaries passed down, no fading photographs tucked into drawers. I don’t even know if there’s anyone left in Ghorband who remembers the names on that family tree.

Decades of war have stripped most of Afghanistan of the simple, human privilege of knowing where they come from. History isn’t just rewritten — it’s erased. To say I know who I am is, in itself, a kind of luxury. One that most of our people have been denied.

All we have are fragments — memory, oral stories, the sound of a name spoken aloud before it vanishes into silence.

I wish I had kept that piece of paper. I wish I had asked more questions. But I’m glad I made the journey. I found enough to know that something lives on — not in records, but in places, in language, in quiet moments in unfamiliar places that suddenly feel like your own.

And sometimes, memory is all we have.

NOTE TO READER:

History has always been taken from us — written by them, for us. The real stories were never recorded. Or worse, erased. My writing is an attempt to bring back to life what the history books left out.

I write these pieces without funding or institutional support, but out of a need to reframe — and reprogram — how we see places like Afghanistan. Not through the lens of war, but through the lives, stories, and histories that rarely make it to you. As a woman from Afghanistan and an aspiring historian, I’m building something that doesn’t yet exist.

If this piece moved you, consider becoming a paid subscriber. It helps keep this work independent — and ensures these stories continue to be told to a global audience.

But most importantly, I hope you’ll read, reflect, and share — because history belongs to all of us.

Thank you for sharing your return to your ancestral homeland with us, Shabnam. This riveting piece I've read twice now, and I will return to it again. It was the first thing I read this morning on my phone, and wanted to reply then, but life... life happened. Now it's evening and I've just reread on my laptop. This beautiful journey to a place I have always been fascinated with, and wondered exactly where it was, and you have given name and place - the where and the how to get there - right here. Beyond that, you have articulated so well the angst of the exile, how even seven generations later a place can feel like home. Do you think you'd ever go back to live there for a while? Is that even possible? I love that the language was familar and you could understanding. The sheer power of people refusing to give up on what is intrinsically theirs - their own language. I have read of the Sogdians when I read about Tang dynasty China - the trade, and the horses. It felt mysterious. I knew it was in modern day Uzbekistan - but you have made this extraordinary place come alive, Shabnam. Thankyou!🙏🏽 Please write more about your ancestral homeland.

Nothing to say except thanks for writing this down