Talkhan: the energy bar that defeated the Soviet Union

How a homemade Tajik energy bar made from walnuts and mulberries became the unlikely fuel behind Afghanistan’s resistance to Soviet occupation.

It is hard to imagine a snack less glamorous.

Talkhan doesn’t melt in the mouth. It doesn’t sparkle in the light of Instagram reels. It’s crumbly, bitter, and slightly oil-slicked from crushed walnuts. But in the high valleys of northern Afghanistan this austere block of pressed mulberries and nuts has done something no chia smoothie or oat-flax bar has ever managed. It brought the Red Army to its knees.

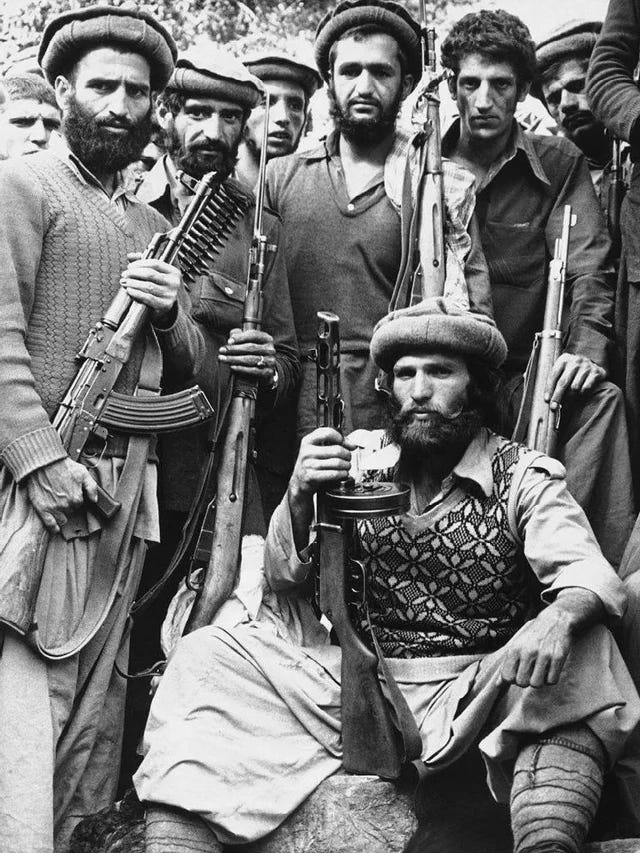

Between 1979 and 1989, Afghanistan became the arena for the Soviet Union’s most humiliating foreign defeat. Over 115,000 Soviet troops were stationed in Afghanistan at the height of the occupation, and more than 620,000 personnel served there over the course of the decade-long war. An estimated 15,000 would never return. The war cost Moscow billions, helped collapse the Red Army’s credibility, and became one of the final nails in the USSR’s ideological coffin. What sustained their opponents? Faith, landscape — and, remarkably, Talkhan.

Its name, Talkhan, is often misunderstood. While some assume it derives from ‘talkh’, the Persian word for bitter, local dialects in Parwan province offer a different story. In these areas, tal refers to naturally sweet, though sometimes astringent, and khan or khani means homemade food or traditional fare. So rather than “the bitter one,” Talkhan more closely means “homemade sweet.” But even when the flavour carries a bitter edge, Persianate cultures have long celebrated such qualities — pomegranate rind, bitter orange, green tea, all are prized for their edge, their staying power.

Talkhan also had religious and medicinal connotations. The mulberry, associated with humility and healing in Persian Sufi texts, was seen as a “pure” fruit, grown without greed or graft. For instance, in Yezidi practices, mulberry trees are considered sacred, often associated with healing and spiritual endurance . Additionally, in some Sufi traditions, trees, including mulberries, symbolise patience and the soul's journey.

When the Taliban fell in 2001, aid agencies arrived with flour, biscuits, and meal kits. But in many rural areas, Talkhan remained. Because it worked. Because it had always worked.

Talkhan’s roots lie not in modern war, but in much older patterns of survival.

It was likely first developed in the highland Tajik regions of northern Afghanistan and southern Tajikistan, where food preservation was not just a tradition but a necessity. The mulberry (toot in Persian) ripens in late spring and spoils fast. Drying it meant extending its life and its use.

By the time of the Ghaznavid empire (10th–12th centuries), there are references in Persian history books to highland communities making sweet cakes from dried fruits and nuts as portable rations. But it is in the 19th and 20th centuries, particularly during the Anglo-Afghan wars, that Talkhan becomes clearly visible in oral accounts as a food of endurance, associated especially with the Tajik populations of Parwan province. These valleys were famously difficult to subdue, largely due to the geography and the stubbornness of their inhabitants.

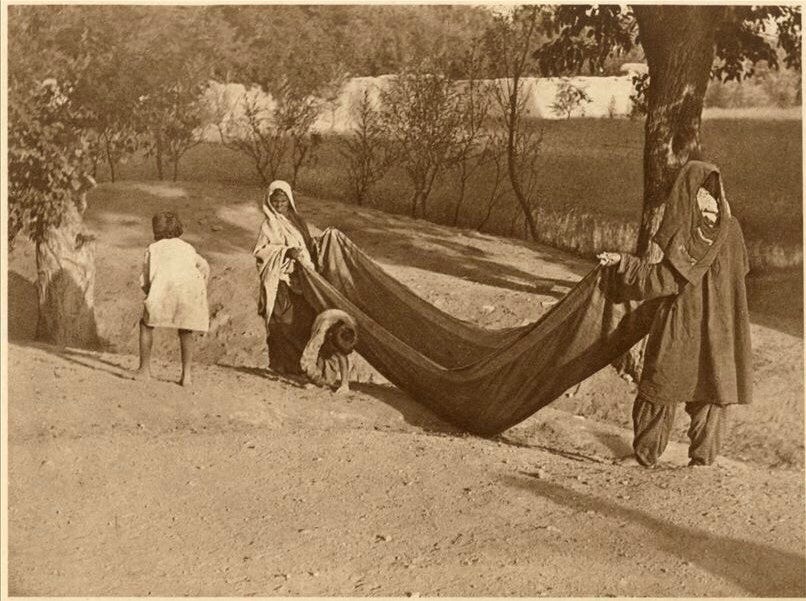

Talkhan was produced without heat, fuel, or formal storage. Villagers would dry white or black mulberries in the sun, grind them into a powder, then mix them with crushed walnuts (and occasionally almonds or pistachios, if they could be spared). The resulting mixture would be shaped into dense slabs or small balls. No sugar. No flour. No additives. And crucially — no spoilage. A block of Talkhan could survive months in the folds of a coat, through frost and gunfire.

During the Soviet occupation, the northern Mujahideen are said to have kept stockpiles of Talkhan. Local women, working mostly at night, would produce it in batches, wrap it in cloth, and distribute it up to the front. A single 100-gram piece could provide up to 500 calories — not bad for something made entirely of native produce.

Soviet forces may have deployed Mi-24 helicopters, napalm, and Spetsnaz commandos, but Afghanistan’s fighters climbed sheer cliffs with Kalashnikovs and Talkhan. It was fuel for insurgency - bitter, local, and irrepressibly unmodern.

Talkhan also symbolised something more than calories.

It stood for a kind of food sovereignty, long before the phrase existed. It was unbranded, unbought, and, crucially, uncolonised. It came not from aid agencies or imports, but from ancestral methods.

One vivid reference comes from a firsthand Mujahideen account recorded by Marcela Grad during the Soviet-Afghan War. After a brutal Soviet offensive, the fighters found themselves starving: “The two hundred mujahideen here have no lunch. … We cannot even find dried mulberries and talkhan (mulberry powder) because all the houses are burned.” Even this most basic sustenance, once made in every home, stored for winter, carried into battle had vanished. Talkhan, in that moment, wasn’t just food. It was the measure of how much had been lost.

Such impressions run throughout veteran accounts collected in works like Zinky Boys by Svetlana Alexievich, where former soldiers recount the psychological shock of confronting fighters who moved silently through snow-bound valleys, fed on little more than this coarse, bitter block — Talkhan.

There are also scattered reports from the other side, Soviet soldiers describing the Mujahideen as “eating stones,” a jab at the hardness of dried Talkhan and its earthy colour, somewhere between dusty brown and burnt red, depending on whether white or red mulberries were used. Some of these details, like Soviet soldiers calling Talkhan “Afghan chocolate”, I’ve heard mentioned in passing, in conversations with researchers and others who’ve studied the war or lived through it. They’re not always easy to trace in writing, but like much of Afghanistan’s history, the truth often lives in memory long before it reaches the page.

While the Red Army relied on canned meat, vodka, and long Soviet supply lines, their opponents somehow kept going just on Talkhan. Astonishing.

Although all of Afghanistan now claim Talkhan as a cultural marker, its origins are unambiguously Tajik. In Ghorband, a variant with black mulberries and wild almonds was used as a winter supplement, sometimes paired with strong tea. In Panjshir, it was often made during the mulberry harvest in June, then pressed into ceramic moulds passed down through families. In Badakhshan, where fruit drying was a regional industry, entire marketplaces would briefly sell Talkhan in different shapes.

These days, you may find some Talkhan in west London in some local Afghan supermarkets, It can travel in tissue paper, hidden in the linings of suitcases, offered by uncles with solemn eyes who say, “Taste this. This is what kept us alive.”

In the diaspora, Talkhan is no longer about survival. It’s a taste-test for identity. For many of us, born in Hayes or Hamburg, it sits somewhere between culinary inheritance and practical joke. But those who understand it know it carries something no processed snack ever could: continuity and heritage.

“It brought tears to my eyes—every time I went to Parwan, my grandmother would make Talkhan for me. We had vast fields of mulberry trees… 🥹”

This is fascinating, Shabnam. I had no idea that talkhan sustained the mujahadeen in such an important way.