The female rulers, rebels and revolutionaries of Afghanistan

History buried them. This International Women’s Day, we dig them back up.

I’ve lost count of how many times I’ve read the same tired words: the women of Afghanistan are voiceless and veiled—uneducated and powerless. As if we’ve spent centuries sitting in the shadows, waiting for the West to hand us a microphone. This narrative latched onto me from childhood, like an ill-fitting dress I was expected to wear. But crack open the past, and the truth is far less convenient— women from my homeland have ruled kingdoms, led revolts, built cities, and outmanoeuvred emperors.

And yet, history books have done us dirty. Our fiercest queens and warriors are reduced to footnotes—if they’re mentioned at all. Well, not today. On the eve of International Women’s Day, I’m tearing up the old script. Let me introduce you to five women who didn’t just exist; they shattered expectations. Leaders, rebels, visionaries. You’ll see that ‘subjugation’ has never been our only story—it’s just the one they keep telling.

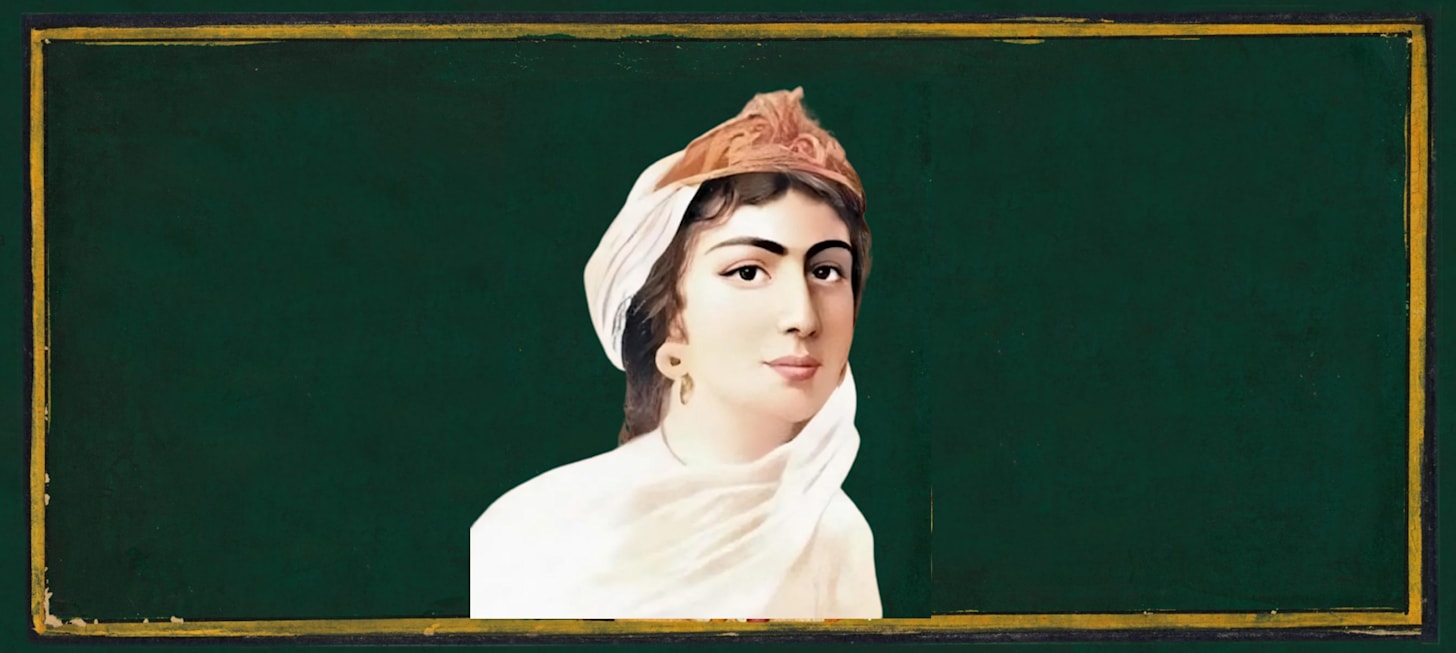

1. Nur Jahan: The Empress Who Slayed Tigers

Born Mehr-un-Nissa in Kandahar to a Persian noble family, Nur Jahan was never going to be the type to blend into the background. By the early 17th century, while most imperial wives were expected to perfect the art of decorative silence, she held a position in the Mughal empire never before filled by a woman: co-sovereign. Historians, with their predictable lack of imagination, have called her “just a consort.” But let’s be real—when your face is on the empire’s coins and imperial decrees carry your seal, you’re not a side character. You’re the whole damn story.

And if political power wasn’t enough, she also had the flair of a Bollywood action hero. One popular tale has her coolly taking down a rampaging tiger—six bullets, perfect aim, emperor in distress. The poets, utterly charmed, dubbed her “the tiger-slayer in the ranks of men,” which, frankly, is the level of reputation we should all aspire to. A woman from Kandahar, eclipsing an emperor in both political acumen and sheer audacity? Yes, please.

But Nur Jahan wasn’t just about palace politics and extravagant hunts—she was the kind of queen who didn’t hesitate to pick up a sword. “In 1626, when her husband, Emperor Jahangir, was taken prisoner by a rebellious nobleman, it was Nur who led her imperial troops to rescue him,” the writer Ruby Lal tells us. Let’s pause on that for a second. While most consorts would have been locked away, praying for their husband’s safe return, Nur Jahan was leading an army into battle to snatch him back. If that’s not main character energy, I don’t know what is.

And yet, for all her military and political genius, history has desperately tried to relegate her to the role of “Jahangir’s favourite wife.” Meanwhile, she was the one governing, managing trade, championing social justice and overseeing foreign policy - keeping the empire from falling apart while her husband indulged in courtly pleasures. She didn’t just wield power—she defined it.

When I first read about her, I thought: Why was I taught about every man who swung a sword, but not the woman who ruled, reformed, and casually slayed apex predators? That’s the energy I want every girl in Afghanistan to carry—the reminder that we don’t just survive history. We shape it.

2. Aisha Durrani: The Poetess Who Built the First Girls’ School in Afghanistan.

Fast-forward to 18th-century Kabul, where Aisha Durrani—married to Emperor Timur Shah Durrani—wasn’t content with palace life and royal niceties. While men busied themselves with conquests and courtly intrigue, she quietly opened Afghanistan’s first known girls’ school. In an era where women’s education was considered either unnecessary or outright dangerous, Aisha had the audacity to teach young girls the Qur’an, poetry, and—most radical of all—the art of thinking for themselves.

When I first stumbled upon her name in a dust-covered book in a Kabul bookshop in 2016, I was intrigued. The book was written in Persian script, so I turned to my uncle and asked him to read it to me. As he spoke, I realised I wasn’t just hearing the story of a forgotten educator—I was uncovering the life of a woman who had slipped through the cracks of history, despite shaping it.

Because Aisha wasn’t just a teacher. She was a poet, a scholar, and an intellectual powerhouse who corresponded with the leading minds of her time. Her Persian verses weren’t just decorative flourishes—they were declarations of a woman who knew her worth. She engaged with scholars and courtiers as their equal, weaving theology, literature, and philosophy into her work. She was well-versed in Arabic, Persian, and Islamic jurisprudence—her mind sharper than most of the men who claimed to rule her world. And yet, how many of us have ever heard her name?

One of the first books ever printed in modern Afghanistan wasn’t some war manifesto or royal decree. It was her collected works. Imagine that. The first major literary imprint of a newly emerging nation was the voice of a woman—one who believed that girls deserved to learn, write, and question.

And yet, we’re still fed the tired line that Afghan women have always been silent, always been passive. Aisha Durrani would have laughed at such nonsense—and then likely written a scathing poem about it.

3. Mah Chuchak Begum: The Widow Who Ruled Kabul

Mah Chuchak Begum, born in Kabul, could have done what widowed queens were supposed to do in 1556—retreat into quiet mourning, fade into irrelevance, maybe embroider something. Instead, she took one look at the political chaos after her husband, Emperor Humayun, died and thought: Absolutely not.

With her infant son too young to rule, she declared herself regent, marched into Kabul’s citadel, and promptly locked out every male governor who thought they’d be running the show. Her stepson, Emperor Akbar—the golden boy of Mughal history—was not amused. He sent armies to unseat her. She sent them back in pieces. She held her ground, fought her battles, and won. Until, of course, someone decided the only way to stop her was to take her life. But even in death, her defiance echoed—her teenage daughter stepped up, continuing what her mother had started.

What makes Mah Chuchak a force to reckon with isn’t just that she was a warrior queen—though the sheer audacity of standing against Akbar deserves its own round of applause. It’s that she knew how to rule. She wasn’t just swinging swords for fun; she was rebuilding Kabul. She booted out corrupt officials and put her people in charge—local leaders loyal to her, men who actually understood how to keep a city from falling apart. She stabilised food supplies, strengthened trade routes, and negotiated truces with warlords, all while fending off armies sent to depose her.

I like to imagine her atop a warhorse, eyes locked on the horizon, fully aware that men would rather kill her than let her lead—but unfazed all the same. Because the thing about women like Mah Chuchak Begum? You can erase them from history books, but you cannot erase their impact. The men who opposed her thought they were playing chess. Meanwhile, she was flipping the entire board.

4. Gawhar Shad Begum: The Queen of Herat’s Golden Age

Herat’s skyline still whispers her name. Gawhar Shad Begum, wife of Emperor Shah Rukh, wasn’t content with the traditional role of a queen—she moved capitals. She convinced her husband to shift the Timurid seat of power to Herat, then transformed the city into a masterpiece. Mosques, madrassas, libraries, palaces—if it was grand, enduring, and breathtaking, odds are, she built it. Those famous minarets that still lean precariously against time in Herat? Hers.

But Gawhar Shad wasn’t just an empire’s architect—she was its strategist. She made sure Persian became the court language, welding a vast, unwieldy empire together through culture rather than conquest. She surrounded herself with the greatest minds of her time—painters like Behzad, poets like Jami—not just because she appreciated beauty, but because she understood influence. Rulers build armies; visionaries build legacies.

And speaking of power, she didn’t just survive the brutal world of Timurid succession politics—she mastered it. When her husband died in 1447, the throne was up for grabs, a dangerous game where the most ruthless always won. But Gawhar Shad had no intention of letting the empire slip into the wrong hands. She maneuvered her favourite grandson into power, ensuring that for a decade, she was the de facto ruler of an empire stretching from the Tigris to the borders of China. While men fought and schemed for control, she simply took it.

But even the most formidable queens aren’t invincible. Well past the age of 80, after years of outmaneuvering rivals, she was finally betrayed. On 19 July 1457, Sultān Abū Sa'īd had her executed—because when history can’t erase a woman’s influence, it tries to silence her instead.

And yet, centuries later, her mark remains. If you ever step into Herat, you’ll feel her—etched into the minarets, humming in the remnants of libraries and palaces, lingering in the spirit of a city that refuses to be forgotten. Every time I walked through Herat’s old city, I heard Gawhar Shad urging me to see past the ruins and remember: a queen once ruled here. And she built something that even time cannot erase.

5. Rabia Balkhi: The Poet Who Wrote in Blood

And finally, Rabia Balkhi—a name that still makes me catch my breath. In 10th-century Balkh, when women’s desires were meant to be whispered, she dared to love openly. Her heart belonged to Bektash, a slave, and for that, she was doomed. Her brother, the emir, was so furious by this forbidden love that he locked her in a bathhouse to die. But Rabia, even in her final moments, refused to go quietly.

Legend says she slit her wrists and, as her life drained away, she wrote—using her own blood as ink, writing her final verses onto the walls. Poetry in its most literal, most heartbreaking form.

But to reduce Rabia to just a tragic love story would be an insult to her legacy. She wasn’t merely a doomed lover—she was the first known female poet to write in Persian, centuries before the world accepted the idea of women as serious writers. She composed poetry in both Persian and Arabic, proving that her intellect was not just rare—it was formidable. Later generations, perhaps uncomfortable with a woman so openly passionate and self-possessed, tried to transform her into something softer. Mystic poets like Attar of Nishapur and Jami took her raw imagery and reinterpreted it through a spiritual lens, rewriting her as a Sufi figure rather than a woman who simply felt deeply. But Rabia was never just a symbol of mysticism—she was a poet of fire, love, and unflinching truth.

Her name still lingers in Balkh, where she is buried near the magnificent mausoleum of Khwaja Abu Nasr Parsa. Her shrine, tucked away beside the resting place of a revered Sufi saint, is a quiet testament to her strange afterlife—claimed by mystics, rewritten by historians, but still, unmistakably, hers.

To me, she’s a reminder that a woman’s voice is never truly buried. That even in death, she spoke. I imagine the power in those final words, scrawled in crimson—her defiance staining the walls, telling us that no prison, no patriarchy, no blade can silence a determined mind.

And yet, history tells us Afghanistan’s women have always been passive, always been silent. Tell that to Rabia Balkhi—the woman who turned her own blood into poetry and left the world no choice but to remember her.

I still remember the BBC News crew in our living room in 2001. NATO had just gone into Afghanistan, and the world was watching, dissecting, pitying. My mother sat in front of the cameras, crying—not just for the past, but for the way we were being seen: as victims, as the defeated, as the women history had silenced. I stood there, nine years old, absorbing the weight of it all. Maybe they were right. Maybe we really were powerless.

But I know better now.

So, the next time someone tries to tell you that Afghan women have always been silent, always been tucked away in the shadows, hit them with this: Queens who ruled, poets who bled, strategists who outwitted emperors, educators who built schools under the noses of men who thought knowledge was theirs alone. Our women have never waited for permission to exist loudly. They have led, fought, built, and dreamed—whether history cared to remember them or not.

And that’s the thing. History has a habit of being selective. Women like Nur Jahan, Aisha Durrani, Mah Chuchak Begum, Gawhar Shad, and Rabia Balkhi didn’t disappear—they were erased, sidelined, scribbled over. But the truth? The truth lives on. It leans against Herat’s minarets, echoes in Kabul’s bookshops, hums in forgotten poetry, and stands tall in Kandahar, where women have shaped dynasties as much as any man with a sword.

And history? We’re taking that back too.

Slaying tigers and writing in your own blood… this is everything I needed. Incredible

HECK YEAH! these are some BADASS WOMEN!