The letter-writer of Ghorband

How an illiterate man taught himself to read using the Persian classics by Rumi, Saadi, Hafez and Ferdowsi —and made history run in my blood.

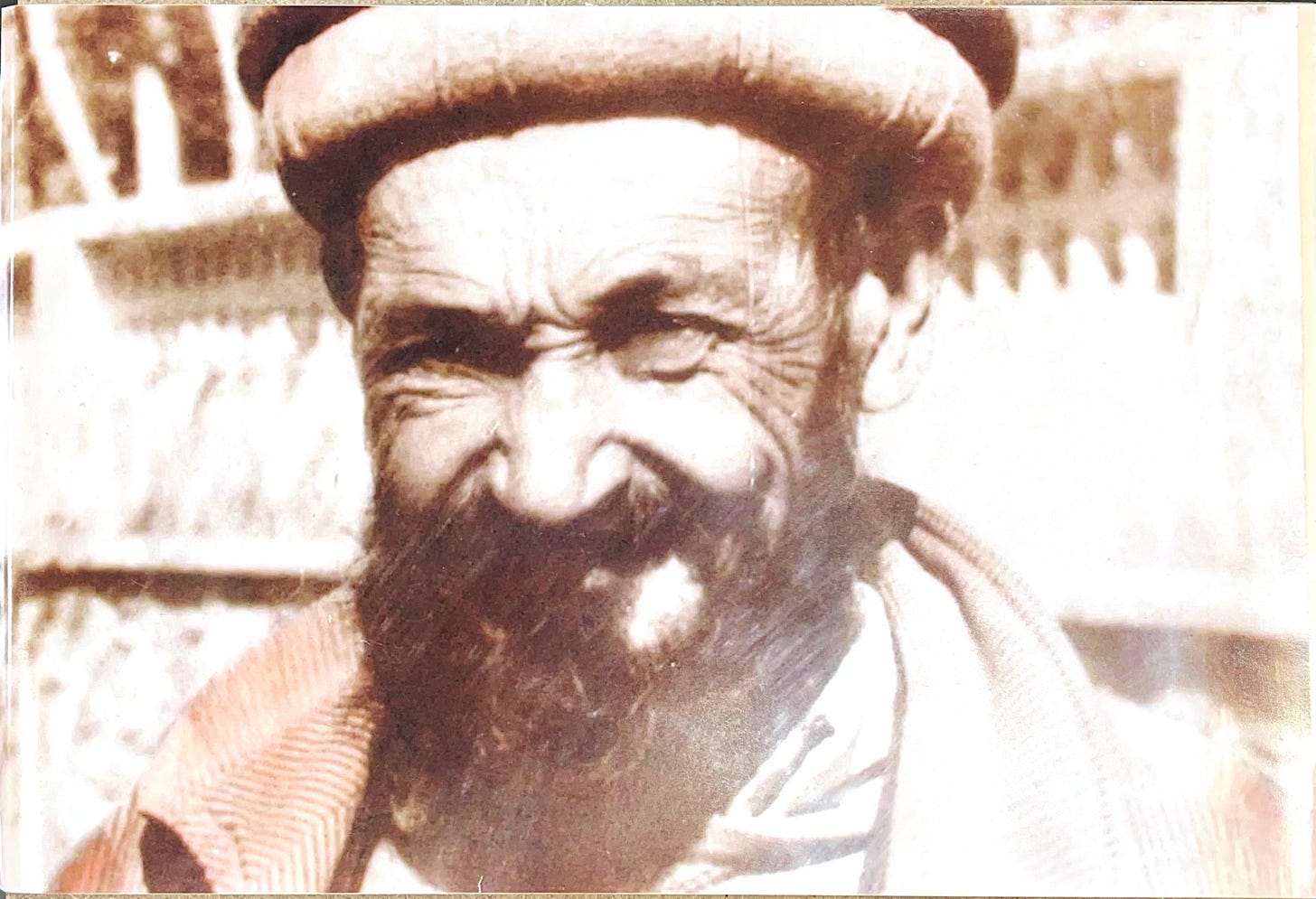

They called him Tawildar.

The keeper. A low-ranking government caretaker. The man in charge of storerooms stocked with working supplies—stacks of paper, ink, typewriters, office chairs, and whatever else Kabul still remembered to send. It wasn’t a title worn with pride, nor spoken with honour. In a country where status was currency and books were as rare as diamonds, being a Tawildar was barely one rung above invisible. A job for a man with no prospects. Someone to be pitied—or mocked.

But they never really saw him.

Because when the supplies were counted and the storage unit padlocked for the night, he’d head for the mayor’s office and sit outside with nothing but a pen, a notepad, and a queue of people waiting to have their stories told.

That’s when he became something else.

That’s when he became an ariza nawees—a writer of petitions, letters and public appeals, the man who gave shape to other people’s struggles, translating the pain of the poor into words that might persuade the powerful.

My grandfather was illiterate—until he wasn’t. He never went to school. Never wore a uniform. Never sat in a classroom.

In an impoverished village where most had never so much as touched a book, where men and women lived and died without ever learning to write their names, he did something almost unthinkable:

He taught himself to read.

And not just to read. He taught himself to read the Persian greats—Hafez, Saadi, Rumi, Ferdowsi—the titans of language and mysticism. He began, like many before him, with the Quran—not reading it at first, but memorising it, word by sacred word. As someone who couldn’t yet decode the page, he learned by heart what the eye could not yet hold. The Arabic alphabet—cousin to Persian—became his gateway.

From there, he slipped into the literary heavens of Persian civilisation. Not through classrooms or tutors, but with a kerosene lamp at night and sheer will. The very texts that scholars devote lifetimes to? He made them his first syllabus.

Imagine it: in a land where language had been stripped from the poor, where books were burned, banned, or simply never there to begin with, my grandfather taught himself literature in the shadows. No teacher. No desk. No dictionary. Just scraps of borrowed books and the hunger to understand. He traced ink with calloused fingers, piecing Farsi together syllable by syllable, mouthing Hafez like a prayer. It was like learning to dance by watching shadows, or composing music by listening to wind. He didn’t learn for prestige—he learned for the survival of the soul.

In a country where literacy was the property of the powerful, where war and neglect had severed the people from their poetic inheritance, what he did was nothing short of a quiet revolution.

Later, when Ghorband became too small, too bruised by hardship, he moved his family to Pul-e-Khumri — the urban centre of central Baghlan Province. The city, such as it was, offered little comfort. They lived in a single small room—his wife, four children, and him—all crammed together like verses in a ghazal. In the same crumbling house lived his brothers and their families, walls thin as parchment, privacy a foreign concept.

By day, he counted staplers and guarded supplies. But after hours, he became something astonishing.

Just outside the mayor’s office, on a battered stool, he set up what I can only call a literacy clinic—not for medicine, but for survival. He read letters for labourers, wrote appeals for widows, turned heartbreak into sentences that might one day reach the desks of power.

He was the translator of desperation, the architect of other people’s hopes. The man you went to when you had no voice but still needed to be heard. In a city where most were illiterate and state power was a walled fortress, he was the bridge between the broken and the bureaucrat. People couldn’t even sign their own names—so they’d press a thumbprint in ink at the bottom of the page, sealing their fate with a fingerprint instead of a signature.

He became known in the city—not as a teacher or a poet, though he could’ve been both—but as the man who would write your letters.

He was the community’s quiet advocate. The keeper of secrets. The voice of the voiceless. A public servant with no pension, no uniform, no nameplate on a door.

His most prized possessions? Not gold. Not land.

A pen. A notepad. A handful of books.

He lived a very poor life. Evenings were often silent with hunger. Some nights, dinner was a heel of bread dipped in black tea sweet enough to rot your teeth—but better that than an empty stomach.

But still—he read.

Still—he wrote.

I remember when my father first told me his story—because I never met my grandfather.

My dad remembers him holding paper like it was holy. The way his lips moved silently when he read Hafez, as though in prayer. He remembers watching from the corner of that cramped room, thinking: this man had built a library inside his mind, brick by aching brick.

He gave away his wages—meagre as they were—to men who wanted to make something of themselves. One opened a bakery. Another, a tailoring business. My grandfather gave them the start-up money from his own salary. Not because he had plenty—he was a poor man. But because he believed that you didn’t need power, prestige, or a formal education to build a better society. Just a pen, a purpose, and the will to help others rise with you.

Even with barely enough money to feed his kids, my grandfather somehow found time to chase Afghanistan’s history. When he could, he’d hop on a bus, buy a ticket, and head off to the next ancient site like it was the most normal thing in the world. He once went all the way to see the ancient Minaret of Jam in Ghor, and another time to Samangan to visit Takhte Rustam. No itinerary, no entourage—just pure, relentless curiosity. While everyone else was trying to put food on the table, he was out collecting ruins and reading Rumi.

And maybe that’s where it began for me.

I often wonder where my appetite for history came from—this obsession with memory, with collecting what has been erased. I used to think it came from books. Or maybe from anger. But now I know: it came from him.

From a man I never met.

A man who taught himself to read in the ruins of a forgotten Afghanistan.

Who carried the ghosts of the great Persian epic, Shahnama, in his breast pocket and whispered ghazals by Saadi like a secret code.

His fire lives in me now. Every story I tell about Afghanistan, every myth I try to recover, every woman I quote, every archive I open—I do it with his voice in my bones.

He wasn’t just a Tawildar.

He was the legacy I never met, but carry every time I write—and the reason I’ll never let Afghanistan’s story be forgotten.

A beautiful piece. Your grandfather would be amazed to hear that on the other side of the world his memory and his work live on.

‘He learned for the survival of the soul.’

That’s the simplest and most eloquent motivation to keep learning, despite any of our circumstances. Very nice piece.