The strange history of Afghanistan's poppy flower

The poppy is not just a flower. It is a lens through which we see how Afghanistan was shaped, exploited, and continually redefined. It tells the story of the nation itself.

In Britain, the poppy is worn each November as a mark of remembrance. It symbolises sacrifice and the human cost of war, evoking the blood-soaked fields of the Western Front. The tradition began after the First World War, inspired by the poem In Flanders Fields, which described how poppies grew among soldiers’ graves. Today, it is a solemn emblem, of honour, loss, and national memory.

In Afghanistan, too, the poppy is bound to war. But its role is not symbolic. It is tangible, cultivated in real fields rather than rhetorical ones. It has funded local economies, enriched militias, and complicated nearly every attempt at peace-building. In one country, the poppy is pinned to a coat. In the other, it is harvested by hand, associated with war economies and the global narcotics trade.

Poppies seem so embedded in Afghanistan’s landscape today that one might assume they have always been there. As old as the mountains, as customary as the rubab. But the poppy is not native. It was introduced, likely more than once, and became naturalised over centuries.

Papaver somniferum, the opium poppy, was first cultivated in the eastern Mediterranean, probably in what is now modern-day Turkey. The Sumerians were familiar with it. They referred to it as the “joy plant” some 5,000 years ago. Joy, evidently, was highly exportable.

By the time Alexander the Great marched east in the 4th century BC, opium was already known throughout the Persian world. Whether it arrived in Central Asia with Greek soldiers or Persian physicians is unclear. But by the early centuries of the Common Era, it had certainly reached Bactria, in what is now northern Afghanistan.

In the centuries that followed, opium was not stigmatised. It was kept in homes alongside vinegar and flour. A grandmother might give it to a child with a cough. A traveller might chew it for toothache or to stave off hunger.

In Persian, it was called teriak, from the Greek theriakē, meaning antidote.

And for many, that is what it was. An antidote to the chronic absence of doctors, hospitals, or any functioning medical system. This was not addiction in the modern clinical sense. It was necessity. It was homemade healthcare.

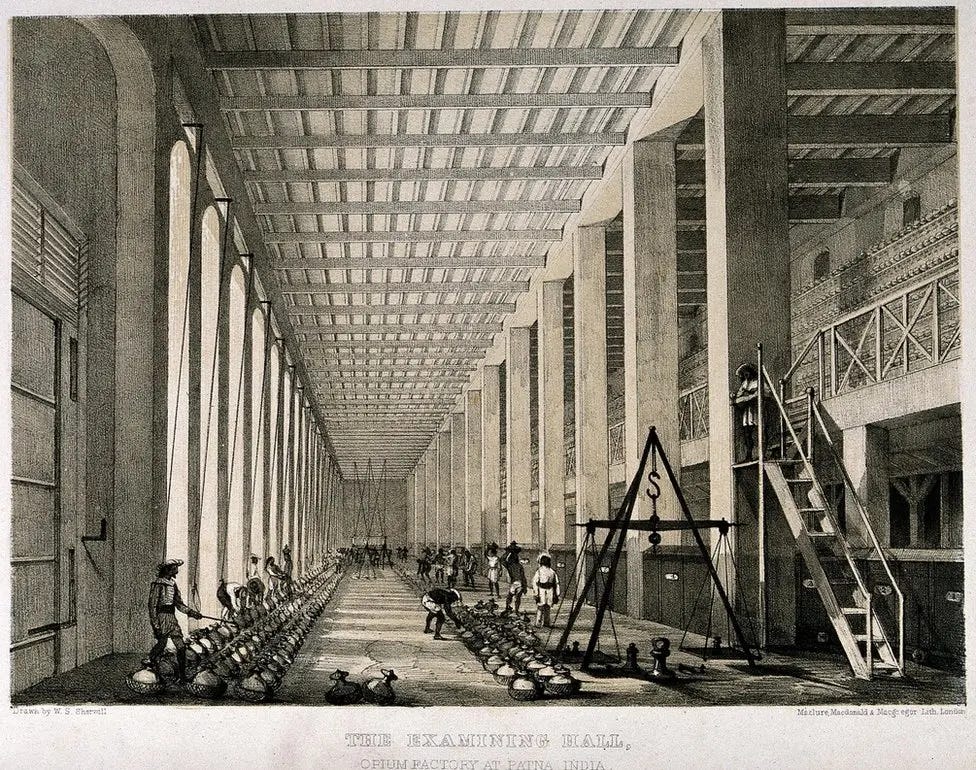

The British, however, had other ideas. In the 18th and 19th centuries, they transformed opium into an instrument of imperial commerce. Large areas of British India, particularly Bengal, Bihar, and the United Provinces, were converted into poppy fields. Indian farmers, under colonial contracts, were compelled to grow the crop.

In cities like Patna, which became one of the main centres of opium processing, the raw resin was refined, packed, and shipped east. From there, it travelled down the Ganges to Calcutta and then to China, where its social and economic consequences were catastrophic. For Britain, this was not informal trade. It was a tightly managed, state-run narcotics industry. Profits fuelled the East India Company and later the Treasury in London.

Afghanistan, famously, was never formally colonised. But it would be a mistake to think that meant it was beyond imperial influence. By the late 19th century, after two Anglo-Afghan wars and the signing of the Durand Line in 1893, Afghanistan had become a British protectorate in all but name. Abdur Rahman Khan, the “Iron Amir”, ruled with British subsidies and a firm understanding of his external limits.

Across the frontier, the British were overseeing one of the largest narcotics economies in the world. Poppies were booming under imperial management. Afghanistan, sharing a porous and poorly monitored border, was not immune. Seeds cross borders more easily than armies. The very provinces adjacent to British India, Helmand and Nangarhar, would in the 20th century become Afghanistan’s main centres of poppy cultivation.

Still, it was not until the 1950s that poppy farming became widespread. When Iran banned cultivation, Afghanistan’s farmers, alert to market gaps, began to plant more. The crop was well suited to Afghanistan’s terrain. It grew in dry climates, required little investment, stored well, and earned more than traditional staples. Even so, the trade remained relatively small and largely domestic.

That changed in 1979. The Soviet invasion brought state collapse, mass displacement, and the destruction of much of the rural economy. In this vacuum, opium became the obvious fallback. Mujahideen commanders needed money. Farmers needed cash. The crop was available, and the markets were ready. By the late 1980s, Afghanistan was on its way to becoming the world’s leading producer of illicit opium. Western intelligence services, focused on defeating Soviet forces, overlooked the implications. Some, as records now show, were willing to look the other way entirely.

Under Taliban rule in the 1990s, opium was initially tolerated and taxed. In many provinces, it was the only part of the economy still functioning. Then, in a surprising move in 2000, the Taliban banned it outright. Production fell by more than 90 percent in a single year. The UN commended the policy.

Following the US-led invasion in 2001, poppy cultivation resumed at scale. The state was weak, the economy fragmented, and international assistance uneven. For many rural communities, it was the only viable source of income. By 2007, Afghanistan was producing over 90 percent of the world’s opium. In Helmand, poppies bloomed beside British military outposts. Foreign troops joked, grimly, that they were there to protect the right of Afghan farmers to grow heroin. No one laughed for long.

Today, the poppy remains a symbol of survival, failure, and contradiction. In the West, it is shorthand for policy collapse, for the futility of development projects, and for the failures of war. In Afghanistan, it is often simply a rational choice in an irrational system. It grows where wheat fails. It pays when the state does not.

Unlike the red poppy worn on British lapels each November, Afghanistan’s poppy is not a symbol of remembrance. It is a reminder of power vacuums, abandoned provinces, and global demand. It is a flower that, once introduced, proved far more difficult to remove than anyone imagined.

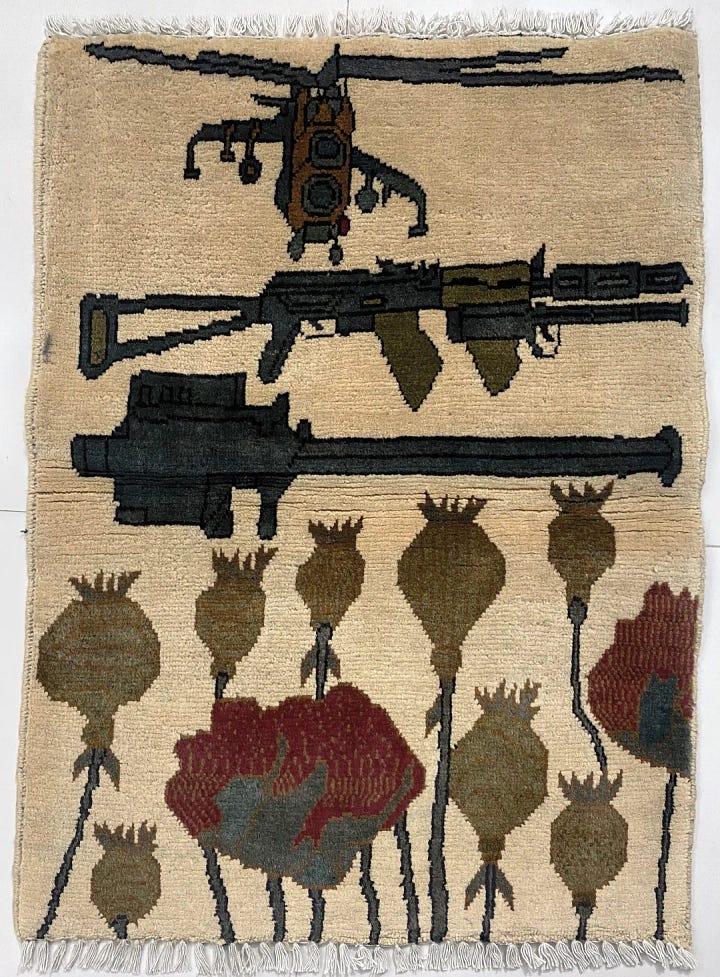

Yet in the country’s craftsmanship, the flower has always carried a different meaning. Floral motifs are stitched into village kilims, carved into wood, painted onto ceramics, and embroidered into wedding shawls. They symbolise beauty, abundance, fertility, and continuity. Long before the poppy became a political crop, the poppy flower were part of everyday design — not to glorify war, but to celebrate life.

And that visual tradition continues.

This month, the British Museum opened an exhibition titled War Rugs: Afghanistan’s Knotted History, exploring how Afghan weavers have responded to decades of conflict through textile design. Some of these carpets now depict poppies, not as fields of innocence, but as signals of political entanglement. Meanwhile, Ishkar has released a new collection of flatweave rugs, made in Afghanistan, whose designs are inspired by the native poppy flower.

For a flower with roots in ancient medicine, imperial trade, and modern warfare, the poppy has come to embody more than conflict. It is a symbol that carries the weight of survival, memory, resistance, and regeneration.

It’s not just a flower. It tells the story of the modern-state of Afghanistan.